The risks of alcohol have long been known. Dr Tony Rao, Visiting Researcher at the Institute of

Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, had suggested: “there is no safe limit

for alcohol when considering overall health risks. The finding of a 7 percent higher risk of developing

any of the 23 alcohol-related disorders for people drinking an average of 17.5 units of alcohol per

week compared with non-drinkers now challenges current U.K. guidance for lower risk drinking, which

recommends no more than 14 units per week (Lancet Psychiatry, 2015 Aug;2(8):674-675. doi:

10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00215-1.)

Anya Topiwala and Klaus Peter Ebmeier (Evidence Based Mental Health, 2018,

(https://ebmh.bmj.com/content/ebmental/21/1/12.full.pdf), had suggested that “Health benefits of

moderate drinking at least for cognitive function are questionable”, since “the reported protective

effects of moderate drinking were due to confounding by socioeconomic class and intelligence”.

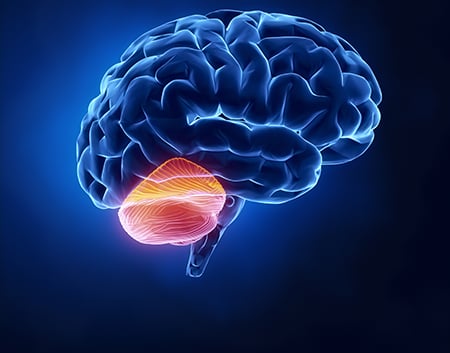

Anya Topiwala et al, in a very recent study (doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.10.21256931)

estimated the relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and brain health, by structural and

functional MRI brain measures. They found that alcohol consumption was negatively linearly

associated with global brain grey matter volume. Also, widespread negative associations were

observed with white matter microstructure and positive correlations with functional connectivity. The

authors concludes that “No safe dose of alcohol for the brain was found. Moderate consumption is

associated with more widespread adverse effects on the brain than previously recognised. Individuals

who binge drink or with high blood pressure and BMI may be more susceptible. Detrimental effects of

drinking appear to be greater than other modifiable factors. Current ‘low risk’ drinking guidelines

should be revisited to take account of brain effects”.

Recently, Sanjay Gupta, American neurosurgeon and chief medical correspondent for CNN, reported:

Even at levels of low-risk drinking, he said, "there is evidence that alcohol consumption plays a

larger role in damage to the brain than previously thought. The (Oxford) study found that this role was

greater than many other modifiable risk factors, such as smoking."

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L92a1ugmfFU) .

As an option for action, WHO, in the line with European action plan, proposes that measures could be

taken to introduce a series of warning or information labels on all alcoholic beverage containers.

World Health Organization finding indicates that most of European citizens believe that alcoholic

beverage labels provide insufficient health-related information. Our campaign “I Care for my Brain”,

www.icareformybrain.org suggests that labelling provides a unique opportunity for governments to

disseminate health promotion messages at the points of sale and consumption. Health information

labels are an inexpensive tool that provides direct information on the risks associated with

psychoactive substance consumption.